Blast From the Past

- Share via

ALBUQUERQUE — “All of my adult life, I have been pulled here. I’ve traveled 1,500 miles, and I’m both sickened and enthralled. It is a soul-shocking place to stand.”

--Message in museum guest book, Los Alamos, N.M.

*

Everyone knows the conventional reasons to go to New Mexico--the enchanting landscape, the mixture of cultures, the arts-rich cities--and my wife and I have enjoyed all of them over the years. But there is another lure as well, the fact that something happened in New Mexico that, as a stone marker simply puts it, “signaled the dawn of a new age and was forever to change the human experience.”

That marker sits near Trinity Site, a desolate spot in the desert 120 miles south of Albuquerque, where, on July 16, 1945, at 5:29:45 a.m., the world’s first nuclear bomb was successfully exploded.

The bomb was not only tested in New Mexico, it was born and raised here. When I learned that Trinity Site’s usually off-limits location--it’s in the White Sands Missile Range--was open to the public on the first Saturdays of April and October, we decided to build a weekend around the landmarks of atomic New Mexico last autumn.

The spark that ignited my fatal fascination with atomic history was a 1981 documentary film, Jon Else’s “The Day After Trinity,” which showed how cultured individuals like physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, well supplied with good intentions and humanistic feelings, built the most terrifying weapon ever known.

Oppenheimer’s love of this part of New Mexico--he owned a cabin in the nearby Sangre de Cristo Mountains--was a key factor in locating the bomb project here. That, and the isolation the mountains and deserts afforded the top-secret wartime effort, which came to be known as the Manhattan Project.

Last October, Trinity Site Saturday coincided with Albuquerque’s hugely popular international balloon festival, where people scan the skies like residents of Metropolis eager for a glimpse of Superman, so finding a hotel room was difficult. (This year the festival runs Oct. 2 to 10. The Albuquerque Convention and Visitors Bureau reported last week that hotel rooms are widely available in the mid-to-budget price range.) My wife and I ended up in a no-frills cubicle in a La Quinta Inn near the airport, which seemed quite in keeping with the serious purpose of our trip.

By the time we got settled in, it was late Friday afternoon. Fortunately, we were close to the first stop on our itinerary, the National Atomic Museum, at Kirtland Air Force Base. The museum is impossible to miss from the shuttle bus that takes visitors there from the base gate. Enormous missiles rise around it like sentries--Minuteman, Redstone, Jupiter, Titan; between them are aircraft built to deliver the smaller models of mass destruction.

Inside, past a well-stocked gift shop--”Get a Half Life, Visit the National Atomic Museum,” the bumper stickers read--most of the space is chillingly given over to benchmark nuclear weapons, such as the MARK (Mk) series, the first atomic bombs to be mass-produced, and the Davy Crockett, a 76-pound portable credited with “bringing nuclear capability to the infantry.”

The most interesting material I saw was the oldest, most notably the duplicate casings of the two atomic bombs that were dropped on Japan: the yellow-and-black plutonium-triggered “Fat Man,” destined for Nagasaki and looking like an enormous, sinister koi, and the smaller, baby-blue uranium-based “Little Boy” that was dropped on Hiroshima.

Though Trinity Site is only 2 1/2 hours by car from Albuquerque, we took the convenient route, the National Atomic Museum Foundation’s guided bus tour, which runs on the two open house Saturdays.

Once Albuquerque and its suburbs were left behind, the scenery consisted of scrub brush and thinly scattered cattle, the exact same spare and spacious beauty Oppenheimer must have seen on his trips to the site. The early Spanish explorers called this bleak stretch of the Rio Grande Valley “Jornada del Muerte,” the journey of death.

Once inside the White Sands gate, the bus’s first stop was at the McDonald ranch house, a simple adobe structure where the test bomb’s plutonium core was assembled. Nothing underlines the primitive nature of the physical side of the bomb’s creation better than the doorjambs leading to the “clean room” designated for assembly, where the hand-painted words “No! No! No!” and “Please wipe feet” were key aspects of the safeguards taken.

Also more than a little terrifying is how little the people involved in making the bomb knew about its power. Some thought all of New Mexico might be destroyed by the detonation, and the New York Times, the only newspaper with a correspondent at the test site, asked for contingency obituaries for all the scientific notables present as well as for its reporter.

With more black humor than some people were prepared for, physicist Enrico Fermi went further, taking bets on whether the blast would ignite the atmosphere and destroy the entire world.

The world wasn’t destroyed, not that day, at least. But the blast was so intense that a local blind woman reportedly saw its light before she heard the sound.

At the gate to the site sits Jumbo, a steel cylinder the size of a truck that weighed 214 tons and was the heaviest item ever moved by rail. It was intended at one point to house the Trinity bomb, the better to capture its plutonium if the blast failed. Jumbo was never used for that purpose and now proves an irresistible lure to kids who race up and down its sides.

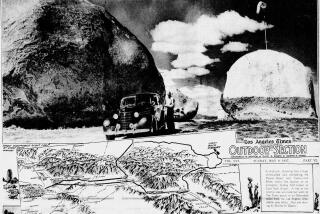

Though the Trinity blast took place more than half a century ago, there is still a radiation warning sign up on the chain-link fence surrounding the site, even though all the literature says Trinity is safe to visit. Also placed on the fence for the semiannual open houses are laminated newspapers and photographs, like the one (pictured on L1) showing the bomb’s core being moved from the McDonald ranch house in a 1942 Plymouth with the doors removed for easy loading.

The explosion made a crater 8 feet deep and a quarter of a mile wide. It generated so much heat that the sand melted, creating a new, glass-like substance given the name Trinitite. The crater has since been filled in, but Trinitite is visible in a protected shed on one side of the blast area.

The only other on-site souvenir of the blast is a small piece of one of the footings of the 100-foot steel tower the bomb sat on that somehow avoided being vaporized with the rest of the structure.

The fenced area is large enough that even with the day’s 100 or 200 visitors, including families with young children and tourists from as far as Germany and Brazil, it never felt crowded. It has, not surprisingly, a spooky, unnerving aura that causes visitors of a certain age to get defensive about the right and wrong of what was done to end the war with Japan. “They started it,” an older woman insisted to her unconvinced daughter, and an older man snapped, “Sure it was terrible. So was Pearl Harbor.”

On Sunday morning we drove to Los Alamos, 35 miles north of Santa Fe, a spectacular ride along narrow, serpentine roads.

When the Manhattan Project began, there was no town of Los Alamos, just the small, exclusive Los Alamos Ranch School for Boys, whose alumni include writer Gore Vidal and baseball executive Bill Veeck.

Oppenheimer and the project director, Gen. Leslie R. Groves, envisioned it as an enclave of about 30 scientists creating the bomb, but by the war’s end the population, which included the staff’s families, had reached 7,000. “The greatest collection of crackpots ever assembled,” is how the general viewed his charges, but to scientists, one wife remembered after the war, “Los Alamos stood for the same sort of thing that Hollywood represents to an aspiring starlet.”

Making things even more odd is that officially Los Alamos did not exist. All mail was delivered to P.O. Box 1663, Santa Fe, the same address that was listed on the birth certificates of the many children who were born there; the average age of residents was 25, and one-fifth of the women were pregnant at any given time.

While a town of 18,000 has grown up around the labs still at Los Alamos, a few of the old Ranch School buildings remain intact. Most impressive is Fuller Lodge, built in 1928 of 771 massive pine logs. Used then as the bomb scientists’ main dining hall, it now houses a small art gallery.

Small though it is, the city (whose bumper sticker plays on New Mexico’s nickname, “Land of Enchantment,” boasting “Los Alamos Has Enchantment Down to a Science”) has two excellent museums. One, the modern and spiffy Bradbury Science Museum, is named after Norris Bradbury, who succeeded Oppenheimer as the director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Among the displays is a letter to Bradbury from science fiction writer Ray Bradbury, who genially complains about getting Norris’ mail and adds, “We are in the same business but on different sides of the street.”

I was more drawn to the Los Alamos Historical Museum, housed in the Ranch School’s former guest cottage. It makes excellent use of a small space and gives a great sense of what life was like in “The Town That Never Was,” where even small children needed photo ID cards and hard-working scientists and their wives relaxed by drinking Moscow Mule cocktails out of copper mugs.

Given that our tour began with the mass-produced weapons that are the modern manifestations of what began at Los Alamos, we decided to end it on Sunday evening by stopping at some little-known sites that showed how tranquil and beautiful the area was half a century ago.

On the drive out toward Santa Fe, we pulled off New Mexico 502 just before the highway crosses the Rio Grande. On the south side of the road is a small and delicate suspension bridge dating from 1924. On the north side, under tall trees, are some outbuildings remaining from a legendary tea room and cafe run by Edith Warner. The place was a kind of refuge for Oppenheimer and other scientists who, according to Peggy Pond Church’s “The House at Otowi Bridge,” booked tables in the tiny, coveted spot weeks in advance.

Going on to Santa Fe, what was our last stop had been the first for everyone who worked at Los Alamos during the war. They had been recruited from around the country and sent to Santa Fe under government orders. They didn’t learn their ultimate destination until they passed through an unmarked door at 109 E. Palace, a street just off the Plaza, where the information was imparted and transportation to Los Alamos was arranged.

The street entrance to 109 has changed in the intervening half a century, but if you walk through the art-filled space to the right of the Rainbow Man, a shop at 107 E. Palace, you will see at the back of the courtyard a plaque next to a simple white screen door. “All the men and women who made the first atomic bomb,” it reads, “passed through this portal to their secret mission at Los Alamos.” That’s how, in the words of one historian, “perhaps the most complex human undertaking in the history of the world” began. How it will end has yet to be written.

Kenneth Turan is The Times’ film critic.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

GUIDEBOOK

New Mexico’s Ground Zero

Getting there: Southwest Airlines flies nonstop to Albuquerque from LAX. America West, Delta and United have connecting service (one change of plane). Round-trip fares start at $198.

Getting around: Trinity Site is at White Sands Missile Range; telephone (505) 678-1134, Internet https://www.wsmr.army.mil. The site is open only on the first Saturday of April and October. By car, take Interstate 25 to U.S. 380 east. (Web site has detailed directions, map.)

On the site’s two open days, the National Atomic Museum Foundation runs guided all-day bus tours from Albuquerque; $30 per person, including lunch; reservations required. Tel. (505) 284-3242. The museum, at Kirtland Air Force Base, is at Wyoming Boulevard and M Street in Albuquerque.

For more information: Albuquerque Convention and Tourist Bureau; tel. (800) 733-9918; for hotel listings, Internet https://www.abqcvb.org. Or the New Mexico Department of Tourism, tel. (800) 545-2070, https://www.newmexico.org.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.