Little windows into the mind of a genius

- Share via

The plague raged across England, Halley’s comet roared through the sky, and an enormous fire ravaged London. Cries went up that this was finally the end of the world.

Meanwhile, in the fens and farmland of Lincolnshire, an odd, antisocial young man taking some time away from his studies at Cambridge University came up with the most radical rethinking of the natural order since the ancient Greeks.

The years were 1665 and ‘66, and Isaac Newton was barely in his 20s. But his musings led to discoveries that remain fundamental to our understanding of the world: the nature of gravity, the properties of light and color. His influence went even further.

“He was the first to unify the celestial and the terrestrial,” says Caltech cultural historian Mordechai Feingold, who has curated “All Was Light: Isaac Newton’s Revolutions,” an exhibition now at the Huntington Library in San Marino.

Until Newton, Feingold explains, there was no reason to believe that the Earth and skies followed the same rules. Moreover, after his breakthroughs, “it became apparent that the human mind could uncover the patterns of the universe, which theologians said was impossible because of the Fall.”

Newton, in short, gave a new audacity to human endeavors. “Everybody wanted to be the Newton of their field. Adam Smith wanted to be the Newton of economics. Jung wanted to be the Newton of psychology.” Science went from a fringe interest to one of the central disciplines.

The Huntington exhibition, which originated at the New York Public Library, has been broken into two parts for its Southland appearance. The first runs through June 12; the second will be up from July 23 to Jan. 1.

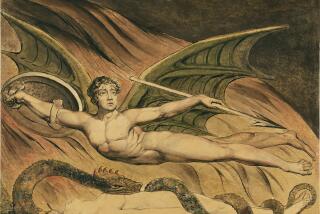

Arrayed in glass cases lining the library’s West Hall are almost 100 items, including some of Newton’s notebooks from Cambridge, a death mask once owned by Thomas Jefferson and Newton’s annotated copy of his masterpiece, the “Principia.” The culture-themed second half will include books by some of his 18th century popularizers, original prints by William Blake and texts showing Newton’s influence on women thinkers.

Apart from the apocryphal falling apple, though, Newton doesn’t have the public image of Galileo, who’s become a kind of science martyr because of his persecution by the Roman Catholic Church, or of Einstein, the mop-topped man of peace.

Paul LeClerc, president of the New York Public Library, was drawn to Newton through his interest in Voltaire, the French philosophe who helped spread Newton’s discoveries across Europe. “One of the reasons I wanted to do the show,” he says, “was that I’m not convinced a lot of people know much about Newton.”

Indeed, by contemporary standards, Newton was a pretty strange guy. Born after his father’s death to a woman who largely abandoned him at age 3, he was brought up by her parents, probably Puritans, during a time of political and religious ferment. Like many of his day, he hated the Catholic Church and saw the pope as the antichrist.

“He grew up during the [English] civil war. It raged around him in the countryside,” says James Gleick, author of a recent Newton biography. “The king was beheaded. It made England different than the Continent. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that Newton could be freer and less given to dogma than if he’d grown up in Italy, let’s say. There was liberty and freedom all around him.”

By 1668, in fact, Newton had become a preeminent scholar at Cambridge. Even so, he somehow went on to lead a long life (he died at 84) without acquiring close friends, collaborators, proteges or lovers. An assistant who worked with him claimed later to have heard him laugh only once in five years -- and then as a sarcastic response to a question.

Instead, he kept his discoveries to himself, engaged in public quarrels with peers and ran several learned bodies like a dictator. In his passion to discover the nature of light, he once spent three days in a dark room to regain his eyesight after staring at the sun through a telescope.

He also went for long periods not eating or sleeping and is thought to have started combing his hair only late in life. Needless to say, he probably died a virgin.

All the same, aristocrats took to placing statues of him in their gardens and ordering that busts of him appear in their portraits. Copies of his work were prominently displayed on desks and bookshelves. “They’re all seeking kinship,” the Oxford-educated Feingold says, “or perhaps seeking some inspiration.”

Ultimately, near the end of his life, Newton became more than a man, more than just a totem that people would plant in their gardens. “The historical Newton largely disappeared,” Feingold says. He became a symbol -- of reason, of science, of tolerant England itself -- to be claimed, contested and fought over.

For the thinkers of the Enlightenment, he represented rational thinking. Artists continued to put him in their paintings -- but in code. “In the 18th century, if you see a rainbow or a prism or a comet in a painting, they’re symbols of Newton,” Feingold says. “There’s no reason to show him.”

Then, in the 19th century, “there was a change of attitude,” says Anthony Grafton, a Princeton University historian, as romanticism developed and aimed to dethrone cold reason. “They blamed Newton for taking the spirit out of the world -- reducing everything to the measured and quantifiable and demonstrable.” Although poets including Alexander Pope had been his champions, Keats, Coleridge and Blake attacked him.

The 20th century, for its part, “largely treated Newton very unfairly,” Grafton says. “You often read statements that we no longer live in a Newtonian universe, since Einstein.” But he notes that only in the case of very small, very large or very rapidly moving objects do Newton’s theories break down. “If you send a rocket to the moon, for instance, Newton does most of what you need.”

In New York, the Huntington exhibition received largely admiring reviews. Some observers, however, commented that Newton was a more complex, perhaps even tragic, character than Feingold makes him out to be.

Gleick, Newton’s recent biographer, described the show in the online magazine Slate as “grand” and “impressive” but incomplete: “We know about Newton’s pathological aloneness, his brush with madness, his obsession with alchemy and theological heresies -- none of which is so much as hinted at in this exhibition, let alone explored.”

Reached by phone, Gleick says he found the show a bit old-fashioned in the way it treats its subject as a hero. And it overlooks an important context, he says.

“Newton was, as the exhibit shows him to be, the inventor of the modern world, in ways that we’re unconscious of. We see the world through Newton’s eyes. But Newton didn’t see the world that way. His world was dark and medieval. And he spent much of his life working on things we consider more or less nutty.”

Feingold acknowledges that Newton could be difficult.

“He had the conviction that he was chosen -- that he brought the Truth, and his rivals chose to ignore it.” (The current edition of the show, he adds, has room to mention alchemy as well as Newton’s attempts to rewrite biblical history.)

But Feingold wants to defend the man from charges of excessive weirdness. He points out, for instance, that alchemy was a branch of chemistry in those days, albeit an experimental one.

“In the history of culture, there are only a few individuals who were able to accomplish what Newton did,” Feingold says. “Darwin, Einstein -- the list is very small. It’s difficult for us mortals to get into the mind of a genius. They obviously obey different rules than we do.”

*

‘All Was Light: Isaac Newton’s Revolutions’

Where: Huntington Library, 1151 Oxford Road, San Marino

When: Noon to 4:30 p.m. Tuesdays through Fridays, 10:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays

Ends: June 12 (Part II runs

July 23 through Jan. 1)

Price: $6 to $15; under 5, free

Contact: (626) 405-2100 or www.huntington.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.