Landscape architect’s mission: Preserve a garden’s soul

By Paula Panich

Landscape architect Rhett Beavers’ Los Angeles garden is a compelling argument against what so many people do when they buy a home: Rip out the existing landscape and start over. Instead, Beavers has spent years pondering what to keep and what to change. Today the backyard is a natural beauty, filled not just with new terraced plantings but also remnants of the land’s past, which includes a 1920s communal orchard. Pictured here: purple tradescantia in the foreground, weathered Adirondacks in back. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Detail of an Adirondack, with maple leaves as a colorful backdrop. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

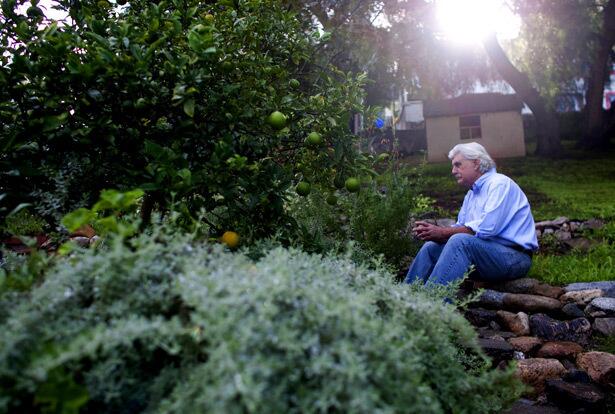

When Beavers uncovered the remnants of a communal orchard behind his 1927 Spanish Revival cottage in Los Angeles’ Echo Park neighborhood, he understood why: The area had been part of Red Gulch, a moniker that reflected the politics of residents who settled here in the 1920s. Though the local political climate might have changed since then, Beavers was impressed with what the landscape still symbolized. He shares his bounty of tangerines, oranges and sapotes with neighbors, and his steeply sloped, 3,000-square-foot garden’s borders with adjacent lots remain unfenced in spots, creating a series of entrances and exits. That’s Beavers, enjoying his garden after a rainstorm. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

The curves of bells contrast with the points of an agave. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Visitors can move easily through plantings and seating areas set on more or less five levels, all carefully organized by the terraced, walled and stepped hardscape. The first change the landscape architect did make was to haul in native stone, which he used to build dry-stacked walls. He brought in more stone for paving, which he dry-laid in sand, to allow water to seep into the soil. He built a dry stream bed for capturing runoff. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

A quiet seating area is surrounded by low-water plants and paved in river rock. Beavers is slowly adding California natives to create habitat for animals, including raccoons, opossums, skunks, squirrels, blue jays, mockingbirds and lizards. A number of older, existing plants and small trees — agave, citrus, sapote and a Western redbud — stayed while Beavers added garden rooms, including one with sages, artemisia and lion’s paw. Seasonal greens flourish on the upper terraces, where arugula serves as an edible groundcover. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

An Australian saltbush sparkles as morning light reflects off rain drops. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Beavers spent the first year hauling things out — trees, rocks, dead plants. But he left terraces built by a succession of owners as well as a patio at the house level, trellised by grapevines. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Beavers says the garden is drought-tolerant at heart. He hand-waters plantings closest to the house and in the edible garden. From a large compost bin he makes planting soil. Like the garden’s past, it all takes time to develop. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“I know this hillside is a part of a larger place, a larger story,” says Beavers, pictured here walking by old fruit trees that help to anchor the terraced landscape. “The most important lesson I learned as a garden builder was not to rush. I let this place speak to me. Now I see the garden every morning as a sea of light.”

More virtual tours: More than 100 photo galleries of California homes and gardens

The Dry Garden: Our weekly column on sustainable landscaping in the West.

Community Gardens: Our weekly dispatches from Southern California’s public plots. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)