Emancipation Proclamation on display

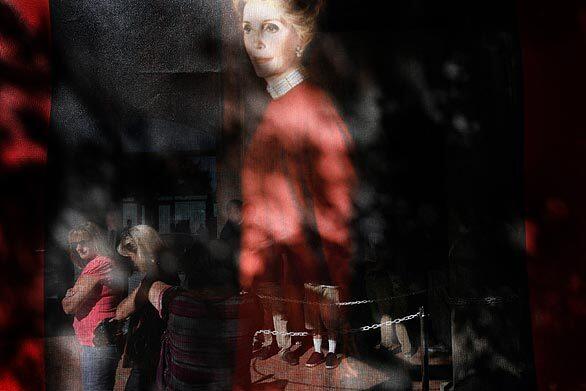

Visitors, seen through a display of former First Lady Nancy Reagan, line up to see the Emancipation Proclamation at the Ronald Reagan Library in Simi Valley. The original document, signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, is on loan from the National Archives and Records Administration. It will be on display through Sept. 23. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Lights were kept low and visitors were prohibited from using flash photography due to the delicate nature of the document. For preservation purposes it is allowed to be on display for less than 48 hours each calendar year. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

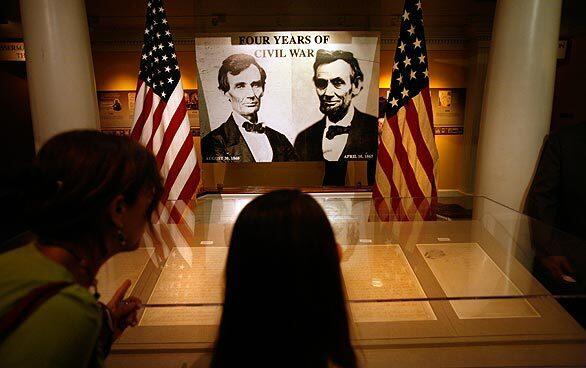

President Abraham Lincoln is reflected in the thick glass display case that houses the document. He issued the Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, after three years of bloody civil war, declaring “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

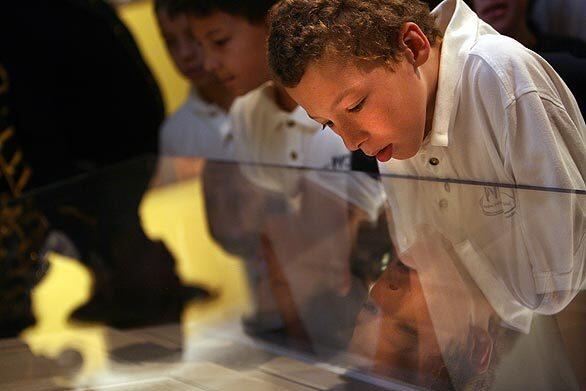

Kyle Randel, 7, a fifth-grader at Pleasant Valley Christian school in Camarillo, gets an up-close look at one of America’s most valued treasures. Though the document will be on display for only five days, the Reagan Librarys exhibit, Forever Free - Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, will run through Oct. 24. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Groups of students from schools in Ventura County are framed by two members of the New Buffalo Soldiers prior to the opening of the exhibit. According to the groups website, the New Buffalo Soldiers of Shadow Hills, Calif., strive to educate and enlighten people of all ages, about the contributions of black men on the American western frontier. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

August Simien Jr., a member of the New Buffalo Soldiers, stands in a Union Civil War uniform during the opening of the exhibit. The Emancipation Proclamation allowed black men to serve in the Union Army and Navy. According to the national archives, nearly 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had served by the end of the war. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)