Road trips from Southern California: New Mexico

Ancestral Pueblo dwellings built high into walls of soft volcanic rock called tuff line a mile-long trail in the park. (Al Cabral / Associated Press)

In the far northwest part of the state, Shiprock, an 1,800-foot tall aptly named formation, is visible for miles, sailing the high plains like a volcanic-rock clipper ship. Look, but don’t climb. It’s sacred Navajo turf. (Marc F. Henning / Associated Press)

A statue of 19th century Archbishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy stands in downtown Santa Fe, across the street from the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

The 1.2-million-acre mesa on the Texas-New Mexico border is notable for having the only pure herd of native pronghorn antelope and the last large tract of desert grasslands in the Chihuahuan Desert. (Steve Capra / Associated Press)

Advertisement

White Sands National Monument is the largest pure gypsum dune field in the world. The national monument offers visitors a drive through the fields, as well as an explanation of how all that sand got there. (Giovanna Dell’Orto / Associated Press)

Don’t think of it as a landscape. Think of it as the best guest ledger in the West, about 200 feet, top to bottom, and made of sandstone.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

This pueblo is one of the largest Anasazi “Great Houses” in Chaco Canyon. The Ketl, with more than 500 rooms and 12 kivas, is a favorite haunt for nature lovers and has a popular Petroglyph Trail, which takes visitors past ancient native rock art.

(Greg Masse / Associated Press)

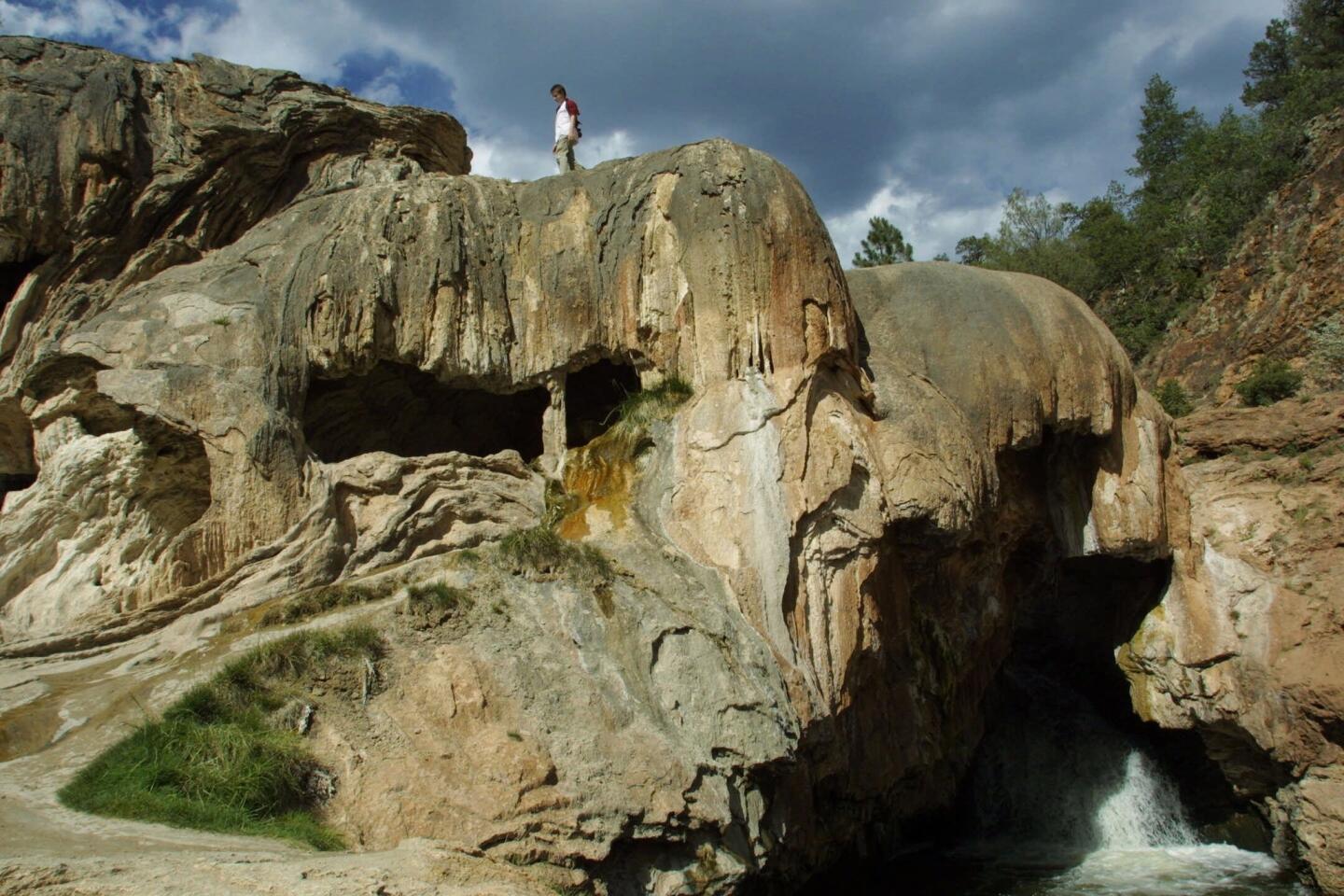

The Jemez area’s history, as with that of much of New Mexico, dates back hundreds and probably thousands of years to the pueblos constructed of the local clay and cave dwellings carved out of the tuff hillsides.

(Pat Vasquez-Cunningham / Associated Press)

Advertisement

This hardscrabble patch of New Mexico became the model for every protected wilderness in the country. America’s first wilderness area -- protected 84 years ago from roads, cars and other modern intrusions -- is still as pristine and untamed as Leopold intended.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)