Population Day 5

Yolanda and Noel Naz, a Philippine couple who live in poverty in Manila, decided early in their marriage to stop at three children. But when the mayor issued an executive order in February 2000 that contraceptives no longer be offered in public health clinics, birth control was out of reach for millions of impoverished residents, including the Nazes. The couple now have eight children, and struggle to support them. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Yolanda and Noel sit in the alley outside their shack with two of their children. They scramble each day to get the money to feed the family. Although she is a Roman Catholic, Yolanda disagrees with the church’s opposition to contraception and is part of a lawsuit challenging the city ban on providing birth control at public clinics. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

The Naz family gathers for a meal, in the same room where everyone sleeps. When food is especially scarce, only the children eat. With 12 million people, greater Manila is one of the most densely populated places on Earth. About a third of its residents live in poverty. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Noel Naz holds one of his children while Yolanda cleans up after the meal. He is sometimes too sick to work, so the family relies on what she can earn selling small packets of shampoo door-to-door. Though more than eight in 10 Filipinos are Catholic, polls show that a percentage nearly that large supports subsidized contraception, an idea vehemently opposed by the church. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Yolanda Naz sits in an alley outside her home. Thirty-nine percent of married Filipinas in their childbearing years say they would like to avoid pregnancy but don’t use contraceptives, commonly citing cost and availability. An estimated 222 million women are in similar straits in Asia, Africa and Latin America, according to other surveys. A study shows that if these women did use modern contraception, it would reduce unintended pregnancies and abortions in the developing world by more than two-thirds. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Yolanda Naz prepares a meal in the family’s two-story shack. The bottom floor functions as kitchen and bathroom and is often infested by rats. The Philippines, an archipelago that is home to 96 million people, has one of the fastest-growing populations in Asia. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Quiapo Church in Manila’s old downtown. The streets around it are known for the vendors who sell concoctions designed to end pregnancy, and for clandestine providers of abortion, which is illegal in the Philippines. Of the estimated 44 million abortions performed worldwide every year, about half are done by the pregnant women themselves or by relatives, traditional healers, charlatans or other nonmedical personnel. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

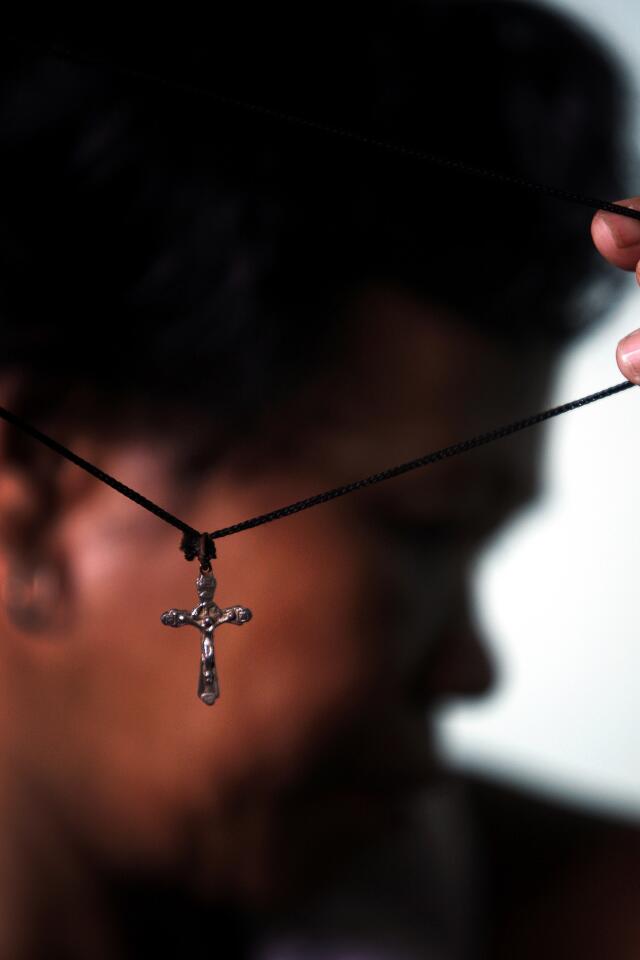

Catholics are sprinkled with holy water outside Quiapo Church. Following Vatican dictates, Philippine bishops oppose the pill, condoms, intrauterine devices and any other “artificial” measure to prevent pregnancy. Instead, they sanction only natural methods, such as abstinence during a woman’s fertile time of the month. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Girls dressed as angels take part in a Flowers of May festival in the Philippines’ Bohol province. The event celebrates the Virgin Mary and promotes chastity. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

The sun lights up the towers of Quiapo Church in Manila. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Newborns are lined up at Dr. Jose Fabella Memorial Hospital in Manila, where as many as 17,000 births occur every year, earning it the nickname “Baby Factory.” “It’s like an assembly line,” said Dr. Ruben Flores, who directs the hospital and its 1,200 employees. “It never stops.” (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Even in the quiet season, women must share beds in the postnatal recovery room at Jose Fabella hospital.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

Medical staff members attend to a newborn in the delivery room at Jose Fabella, which has one of the busiest maternity wards on the planet. The Philippines, with a birthrate of more than three children per woman, is on track to reach 155 million people by 2050. That would place it among the world’s 10 most populous nations. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Several deliveries are often occurring simultaneously at Jose Fabella. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A newborn screams for attention while her exhausted teenage mother sleeps. On the bed is a brochure about family planning left by hospital personnel. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Erlinda A. Casitas, a practicing Catholic, is also a hilot, one of the massage abortionists who perform a large share of the estimated 475,000 illegal abortions in the Philippines every year. “First what I do is to pray to God and ask for forgiveness,” she said. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

“Pampa Regla,” which means “induce menstruation” in Tagalog, is an herbal brew used to cause abortion. It is sold by street vendors just outside the entrance to Quiapo Church in Manila. Cytotec, an ulcer medication sold on the black market and used to bring on uterine contractions, is sold as well but kept out of sight. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A mother feeds her children in the squatters village atop the dump in the Tondo district of Manila, where hundreds of thousands reside as scavengers and recyclers. Shantytowns have sprung up beneath bridges, beside high-rises, on landfills. The living have even taken up residence beside the dead, in cemetery vaults and among the tombstones. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A slum at water’s edge in Manila. The densely packed, unsanitary communities are sprouting faster than the high-rises in wealthier parts of town and are growing at an alarming rate worldwide as people migrate to cities in search of a better life. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Barefoot children play in the sludge of the Tondo dump, where residents eke out a living by sifting through the refuse. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Haphazardly constructed homes are the norm in Tondo. Manila’s former mayor Jose “Lito” Atienza, who ordered the removal of contraceptives from public clinics a dozen years ago, said he sees economic potential in a growing population. “When you have more people, you have a bigger labor force,” he said. “You have a bigger social security base. You have more productivity. You have more consumption. More production. The whole cycle of the economy moves faster.” (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A mother holds her child behind a door made from a mattress box spring in the Tondo dump. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Nelly Ariola, 28, pregnant with her fifth child, looks down at the casket of her son Kelly in Manila. She and her husband walked more than a mile to a government hospital after the infant fell ill, apparently with pneumonia brought on by malnutrition. The couple could not afford transport to the hospital and, after he died, were struggling to come up with the money to bury him. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Kelly Ariola was just under a year old when he died. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Fishing boats are plentiful in the waters surrounding Bohol island, but collecting sufficient bounty from overfished waters is increasingly difficult as the Philippine population grows. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A Philippine workman offloads vegetables and other food to a densely inhabited outer island, where residents cannot grow or catch enough food to eat. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

As population growth puts more pressure on the sea’s resources, residents in Bohol have begun using illegal fishing methods, such as throwing dynamite into the water. This dugong, a marine mammal, was thought to have been a casualty of dynamite fishing. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Generio Apolona and some of his children scour the Bohol mud flats at low tide to look for tiny crustaceans and other bait he could use to catch fish for the family. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Generio Apolona lands a small fish, though it was one of the biggest of the day. As he labored with his hand line, an explosion of dynamite was audible nearby — the sound of desperation among fellow fishermen. On this day, his catch wasn’t enough. His pregnant wife sold the fish to buy rice, so she and their seven children would have something to eat. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)